Download the Report PDF:

Download1. INTRODUCTION

As social media companies face the need to curb the spread of rapidly evolving online harms on their platforms, “community moderation” has emerged as a popular experiment for addressing false, misleading, or “confusing” content. X, whose Community Notes system has invited users to collaboratively annotate posts for years, was at the helm of this model of moderation, with other tech giants now jumping in to implement their own, similar versions. Meta rolled out user-driven feedback tools based on X’s open-source software in April 2025. A few weeks after, TikTok announced Footnotes, its pilot to crowdsource context.

Though Community Notes has become a flagship model for decentralized content moderation, the approach itself is hotly debated. Supporters call community-driven content moderation a democratic alternative to opaque, top-down decision-making. Critics argue this type of system shifts too much responsibility onto the users and is too slow and unbalanced to meet the scale and speed of today’s information crises.

To offer a clear understanding of how Community Notes actually works, what could be improved, and the potential of this model for strengthening a healthier online ecosystem, the Digital Democracy Institute of the Americas (DDIA) set out to analyze the entire public dataset published by X between January 2021 and March 2025: more than 1.76 million notes written in 55 languages and available on the platform’s website.

The first of multiple studies DDIA hopes to conduct on Community Notes, this analysis focuses on the structure, operational mechanisms, and distribution of notes in English and Spanish on the platform. As other tech companies consider whether and how to build their own community-driven moderation systems, the findings presented in this report shed light on the flagship model’s pitfalls, performance, and potential.

2. KEY FINDINGS

ABOUT X’S COMMUNITY NOTES PUBLIC DATA

What’s in the data: X received 1.76 million Community Notes across 55 languages between January 2021 and March 2025.

What’s positive: The data is technically public and accessible for download, a rare move among social media platforms.

What’s challenging:

The dataset is massive and tough to analyze effectively at scale without the use of cloud-based tools (e.g., BigQuery).

Crucial metadata (including language tags, geographic information, and contributor demographics) is absent.

Free access to X’s API has been closed since 2023 (to everyone), which means those studying the dataset can only see which Community Notes are connected with which X posts individually.

Why it matters: These limitations make it hard for external researchers to fully evaluate the system’s reach, fairness, and impact.

ABOUT NOTES SUBMITTED TO THE PROGRAM

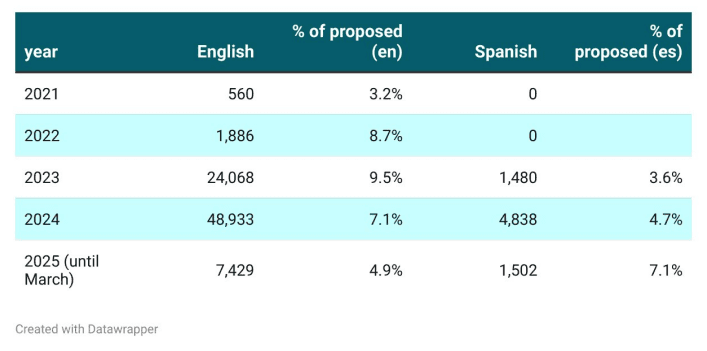

What’s in the data: English and Spanish are the two most-used languages in Community Notes. 1.12 million notes were submitted in English and 165,000 in Spanish between January 2021 and March 2025 - English accounted for 63.8% of all notes, Spanish for 9.3%.

What’s positive:

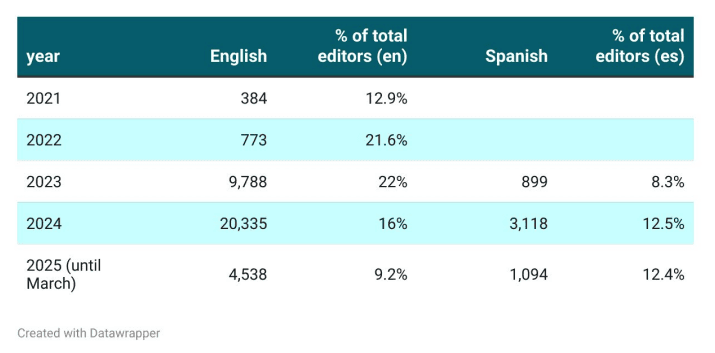

The number of contributors submitting Community Notes doubled in both languages in 2024 compared to 2023. The degree to which contributors are participating is also expanding.

Spanish-language participation rose sharply in 2023, after global expansion of the program, and stabilized in 2024 at around 8,000-11,000 notes per month.

What’s challenging: Language disparities remain stark. Spanish submissions remain under-represented. And, while higher degrees of participation and more notes submitted could be a positive development, this also impacts bottlenecks.

Why it matters: Information online travels between platforms in a cyclical and borderless manner. Addressing harms mostly in English does little to curb the spread of problematic content at scale.

ABOUT NOTES PUBLISHED BY THE PROGRAM

What’s in the data: 82,800 notes were published in English between January 2021 and March 2025 (7.1% of all submissions). 7,800 notes were published in Spanish (4.7% of all submissions). To be published, a note must:

Be seen and rated by an unspecified number of contributors.

Reach a “stable consensus” on usefulness across contributors with differing profiles, though X does not clearly define what qualifies as sufficient diversity of perspectives among contributors or how much agreement is needed to reach stable consensus.

What’s positive: The time it takes a note to go from submitted to published in a definite way has improved, from 100+ days in 2022 to an average of 14 days in 2025.

What’s challenging:

A 14-day lag is still too slow to counter the rapid viral spread of online misinformation and other online harms.

The backlog of notes seems to be growing. Contributors are submitting new notes faster than existing ones are being rated, leaving many notes in limbo.

ABOUT NOTES SITTING INSIDE THE PROGRAM

What’s in the data:

77,108 English notes (17%) had never received any rating by early 2025.

58,859 Spanish notes (15%) were also unrated during the same period.

Factors contributing to notes being unrated seem to include: timing, volume, and limited exposure to contributors.

What’s positive: The share of unrated Spanish-language notes is decreasing over time, indicating potentially improved visibility of notes inside the program and higher contributor engagement in that language.

What’s challenging:

The share of unrated English-language notes is growing over time, leading to a backlog. Notes that are not seen by contributors after a while are not validated or published, weakening the program’s promise of collective moderation.

There does not appear to be a system in place to manage or retire notes that are never reviewed, in either language, raising concerns about fairness and long-term system efficiency.

ABOUT TOP CONTRIBUTORS

What’s in the data:

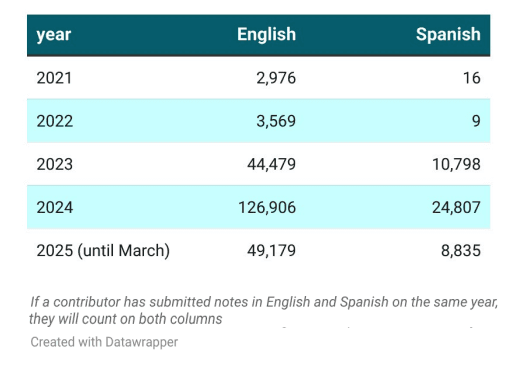

Between 2021 and March 2025, 167,386 contributors submitted notes in English; and 31,034 of them (18.5%) have had at least one note published.

Between late 2022/early 2023 (when Spanish-language contributions became available) and March 2025, 33,340 contributors submitted notes in Spanish; 4,583 of them (13.7%) had at least one note published.

Contributors are anonymized through hashed IDs, a standard practice in privacy protection. There is no data available about contributors’ locations, identities, or profiles. Language use was inferred by DDIA through note content (see Methodology).

What’s positive: Contributor participation is high in both languages, and a qualitative analysis of top contributors shows some are clearly committed to engaging with specific content areas like scams or political misinformation.

What’s challenging:

By and large, notes submitted in Spanish are rated and published less frequently than notes submitted in English.

The system has allowed for at least one potentially automated contributor to engage in the program, raising questions about quality control and editorial balance.

Lack of demographic data about contributors limits insight into contributor diversity, and the system’s ideological representation.

What’s notable:

The top English contributor seems to be an automated account targeting crypto scams, with over 43,000 submissions and a low success rate of publication (3.1%).

The top Spanish contributor focuses on political misinformation, mostly about Venezuela, and submits fewer notes than the top English collaborators.

3. METHODOLOGY

The Data

This analysis is based on publicly available data from X’s Community Notes program dating from inception of the program in January 2021 to March 14, 2025, when DDIA downloaded the full set of data. The dataset includes notes submitted between January 28, 2021, and March 12, 2025, and is composed of four main tables (spreadsheets):

‘Notes:’ 1,764,939 entries (917.2 MB), each representing a unique annotation (a note) attached to a post.

‘NoteStatusHistory:’ 403.88 MB, documenting the progression of each submitted note through the system.

‘Ratings:’ Over 276 million user evaluations (81.45 GB), reflecting whether notes were marked as “helpful” or “unhelpful.”

‘UserEnrollment:’ 134 MB, containing limited contributor data such as enrollment dates and activity thresholds.

The Approach

Given the size and complexity of the dataset, standard tools like Microsoft Excel were insufficient for analysis. DDIA’s research consultants used Google BigQuery, a cloud-based platform capable of handling large scale SQL queries, to manage and process the data efficiently.

Language identification was conducted using Python’s langdetect library, which detected 55 languages in the dataset. English emerged as the dominant language, followed by Spanish, Japanese, and Portuguese. A manual review of 2,000 notes confirmed the accuracy of language detection with 99% confidence.

Research Focus

The analysis centered on three key areas:

The structure and limitations of X’s Community Notes system and the public dataset

Participation and publication dynamics, with a focus on differences between English and Spanish

Behavioral patterns of top contributors, including output volume and pace of submissions

Initial exploration focused on the scope of public data – how much is accessible and where critical gaps exist. DDIA also examined the evolution of English- and Spanish-language note activity over time, including rates of submission, growth in the number of contributors taking part in the program, and the degree to which notes were successfully published. The behavior of contributors was also assessed. DDIA was able to analyze contributors’ levels of activity and whether patterns suggested coordinated or automated behavior.

What is made publicly available by X does not include metadata for geographic location, author profile, and language labels. The absence of this information poses significant challenges for assessing regional participation and the profiles of contributors. DDIA endeavors to develop methodologies for analyzing the content of notes and the content of the X posts that received those notes in subsequent studies.

4. UNDERSTANDING X’S COMMUNITY NOTES SYSTEM

The Origin and Evolution of the Program

Community Notes, formerly known as Birdwatch, is X’s flagship initiative to crowdsource content moderation. Launched in English in the United States in 2021 (a few weeks after the January 6, 2021 attacks on the U.S. Capitol) and expanded globally at the very end of 2022 (under Elon Musk’s supervision and after the Russian invasion of Ukraine), the program allows eligible users to add context to public posts that may be misleading.

For the first two years of the program’s existence, mostly only notes in English were posted, and mostly users addressed content related to the United States. In 2023, the program opened its doors for contributors from other countries, including Brazil and Mexico, leading to a surge in the submission of notes in languages other than English.

Who Can Participate and How Contributions are Made

Participation in the Community Notes program is open to X users with at least six months on the platform, a verified phone number, and no recent violations of the platform’s Rules, Terms of Service and Privacy Policy.

While X claims to admit new contributors frequently, it does not disclose how long users wait or how many are currently pending admission.

The platform informs that it usually selects contributors from country-specific waitlists to promote ideological diversity. All notes and user activity are public and anonymized to protect identities.

A Community Note’s Life Cycle, from Submission to Publication

Social media content moderation has traditionally been done by companies’ trust and safety teams in accordance with the companies’ internal policies and decisionmaking processes. According to X, the Community Notes program is driven by community consensus and a diversity of perspectives. Both depend on the supposed impartiality of user contributions.

Importantly, particulars on the profiles or ideological leanings of the contributors, how many contributors need to rate a note, how much agreement is needed from contributors for consensus on a note to be reached, and how many “differing viewpoints” are sufficient for that conclusion to be reached, are not clearly available.

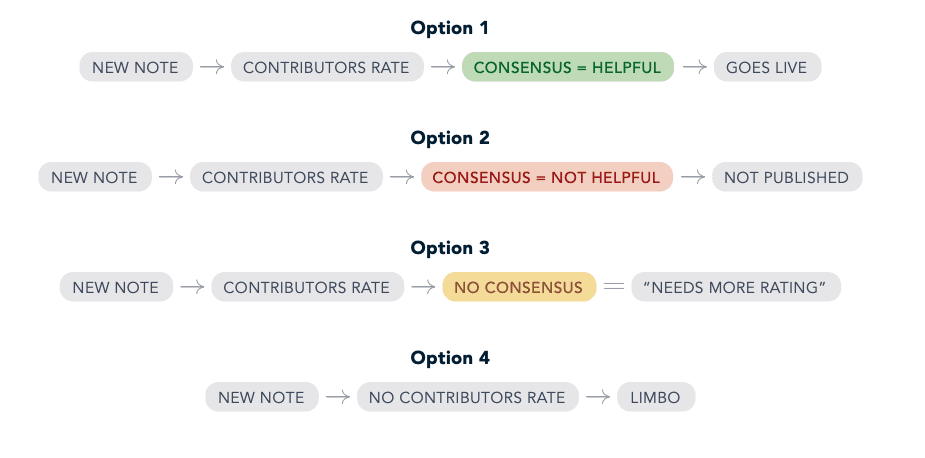

The steps from submission to publication of a Community Note are as follows:

STEP 1 - Submission: Community Notes contributors create notes offering context or corrections in response to specific X posts.

STEP 2 - Rating: Once a Community Note is proposed by a contributor, said note is put in front of other contributors by X’s internal system, and other contributors are asked to rate the note as “helpful” or “not helpful.”

STEP 3 - Review: For a note to be published, it must receive a sufficient number of “helpful” ratings compared to “not helpful” ones, meeting a specific threshold established by the platform. That threshold is not disclosed and could differ per post.

If users with differing viewpoints agree a note is helpful enough (it is not clear what X constitutes as enough), the Community Note is made public on the platform.

If users agree the note is not helpful, the label on the note changes to “not helpful.”

While consensus on the usefulness of a Community Note is pending, the note is classified as “needs more rating.”

STEP 4 - Publication: Once published, the note is attached to the original X post, making it visible to users.

The life cycle of a Community Note can thus look as follows:

5. SUBMITTED NOTES: ENGLISH VS. SPANISH

English Dominates the Program

Since 2021, 1.76 million notes have been submitted to X’s Community Notes program. Nearly two-thirds (63.8%) were written in English, while only 9.3% were in Spanish – a disparity largely explained by the program’s initial U.S.-only rollout. For its first two years, Community Notes operated almost exclusively in English.

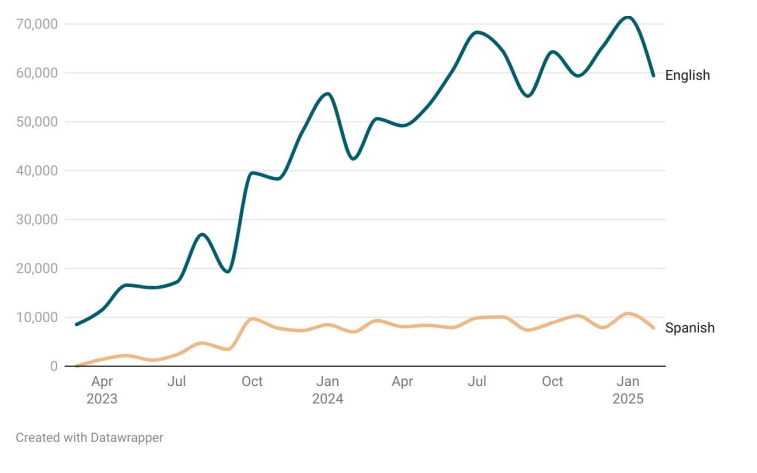

Spanish Growth Slows After Early Surge

Spanish-language participation spiked in 2023 when the program expanded to users outside of the United States. But after that initial surge, growth leveled off. By 2024, monthly contributions in Spanish ranged between 8,000 and 11,000 in a stable way. In English, submissions continued climbing steadily month over month.

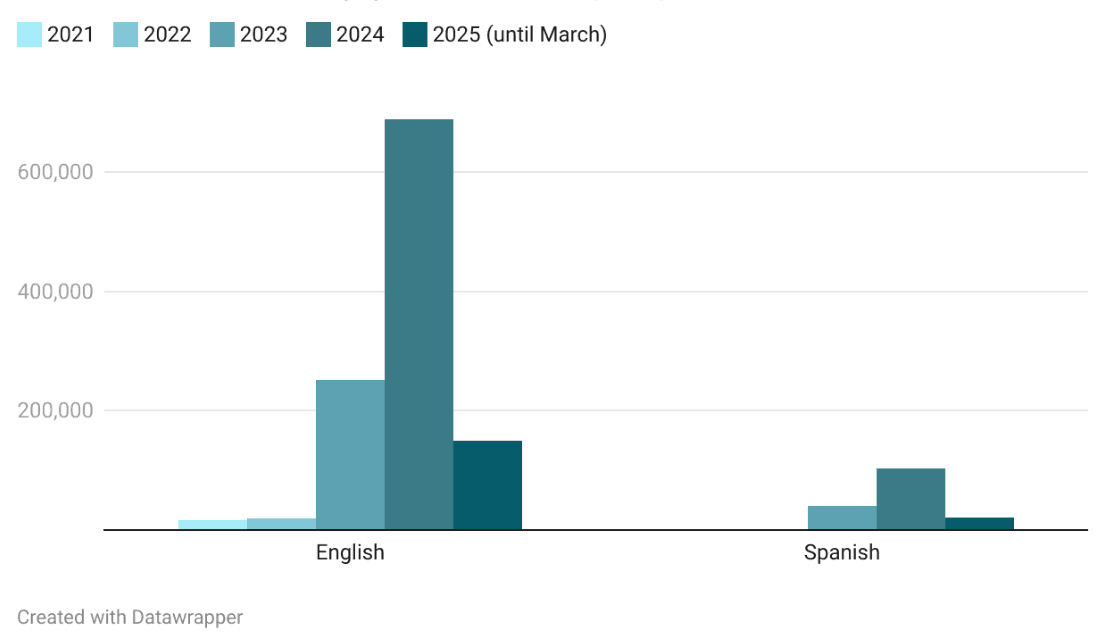

Notes Submitted by Year and Language

Notes Submitted by Month

The Number of Contributors Participating in the Program Is Climbing

User participation in the Community Notes program is rising across both languages. In 2024 alone, more than 126,000 contributors submitted at least one note in English, more than double the total from 2023. In Spanish, nearly 25,000 users submitted notes, also more than doubling year over year. Early 2025 data indicates the upward trend is continuing.

Unique Contributors by Year and Language

6. PUBLISHED NOTES: RATINGS, TIMING, AND BARRIERS

Most Notes Are Never Published

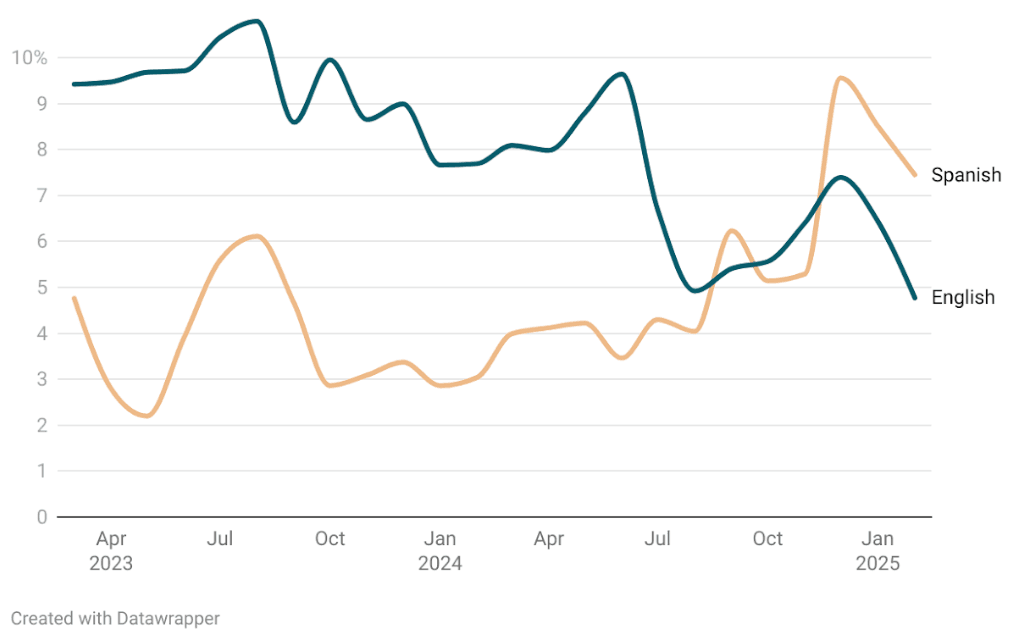

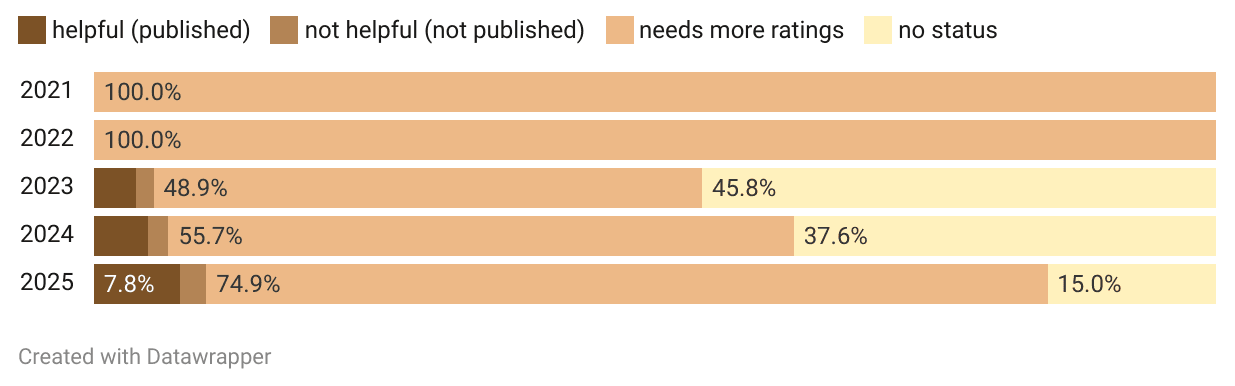

Less than 10% of submitted notes are ever published, usually for lack of consensus about their “usefulness” during rating. In English, the publication rate dropped sharply, from 9.5% in 2023 to just 4.9% in early 2025. Spanish-language notes, while historically less successful in reaching publication, have shown improvement: publication rose from 3.6% to 7.1% over the same period.

Publishing Is Faster Than It Used to Be – But Still Too Slow for What the Internet Requires

The time it takes for a note to go live has improved dramatically over the years, dropping from an average of 100+ days in 2022 to just 14 days in 2025. But even this faster timeline is far too slow for the reality of viral misinformation, timely toxic content, or simply errors about real-time events, which spread within hours, not weeks.

Notes Published by Year and Language

Spanish Users Still Lag, English Faces Bottlenecks

Spanish-speaking contributors continue to have lower success rates of publication of their notes overall, despite a recent uptick in Spanish-language notes and contributors. Meanwhile, in English, bottlenecks are starting to emerge – too many notes for raters to choose from and a larger volume of English-language notes and contributors submitted overall are making it harder for notes to reach the publication threshold. More users are contributing, but fewer notes seem to be breaking through.

% of Notes Published, by Month and Language

Number and Percentage of Contributors Whose Notes Were Published

7. NOTES LEFT UNRATED

Thousands of Notes Go Unrated

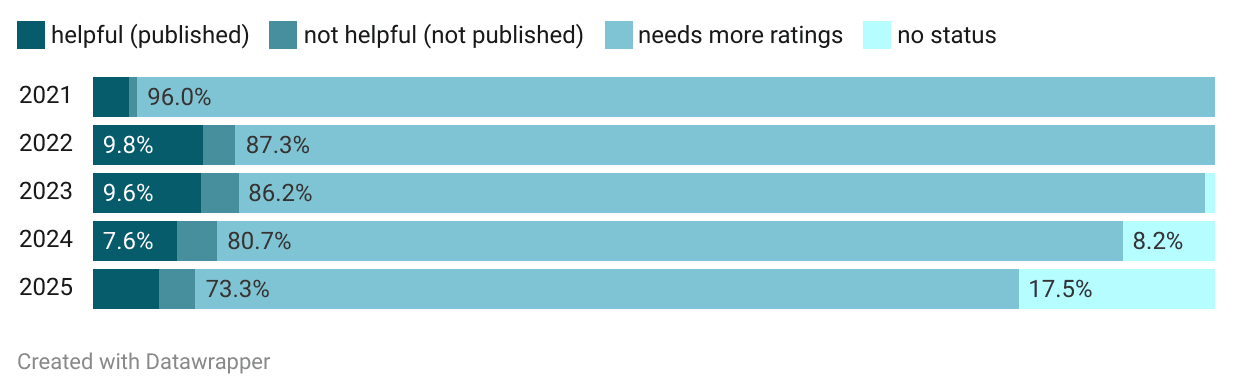

A significant share of submitted notes never receive a rating inside of X’s Community Notes. In 2024, 8% of English-language notes were never rated. By early 2025, that number had more than doubled to 17%. In Spanish, 37% of notes submitted in 2024 went completely unrated. This could mean they were never seen, as well as never assessed.

Visibility Could Be the Weak Link

As the volume of notes submitted grows, the system’s internal visibility bottleneck becomes more apparent – especially in English.

Despite a rising number of contributors submitting notes, many notes remain stuck in limbo, unseen and unevaluated by fellow contributors, a crucial step for notes to be published.

Volunteer-Based Model Shows Its Limits

By the first quarter of 2025, more than 17% of English notes and over 15% of Spanish notes had yet to be viewed by a single contributor. Without a mechanism to surface or retire overlooked notes, the backlog continues to grow, putting the credibility and efficiency of the system at risk.

Distribution of Note Status in English

Distribution of Note Status in Spanish

8. CONTRIBUTOR BEHAVIOR AND TOP EDITORS

As previously noted, the discontinuation of free API access to X has limited this report’s ability to offer largescale content analysis. Consequently, the primary focus remains on contributor behavior, rather than the content of notes or X posts. Nonetheless, to provide a preliminary view of content trends, DDIA conducted a manual review of notes submitted by the top 10 contributors in both English and Spanish. Key findings from this qualitative assessment are outlined below.

English: High Volume, Low Impact from Automated Activity

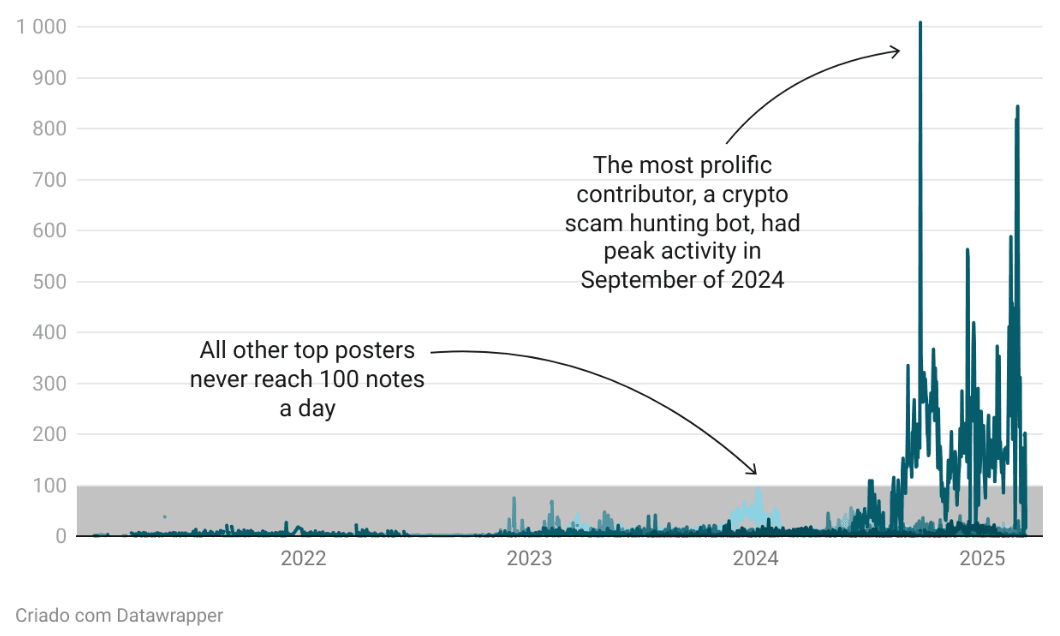

The most prolific contributor in English seems to be a bot-like account dedicated to flagging crypto scams. It submitted more than 43,000 notes between 2021 and March 2025. That volume does not appear to have translated into more notes being published: only 3.1% of those notes went live, suggesting most went unseen or failed to gain consensus.

Other top English contributors focus on topics like vaccine misinformation, with varying levels of success. Their publication rates range widely, from just 3.1% to as high as 45.7%.

Daily Activity of the Top 10 Contributors in English

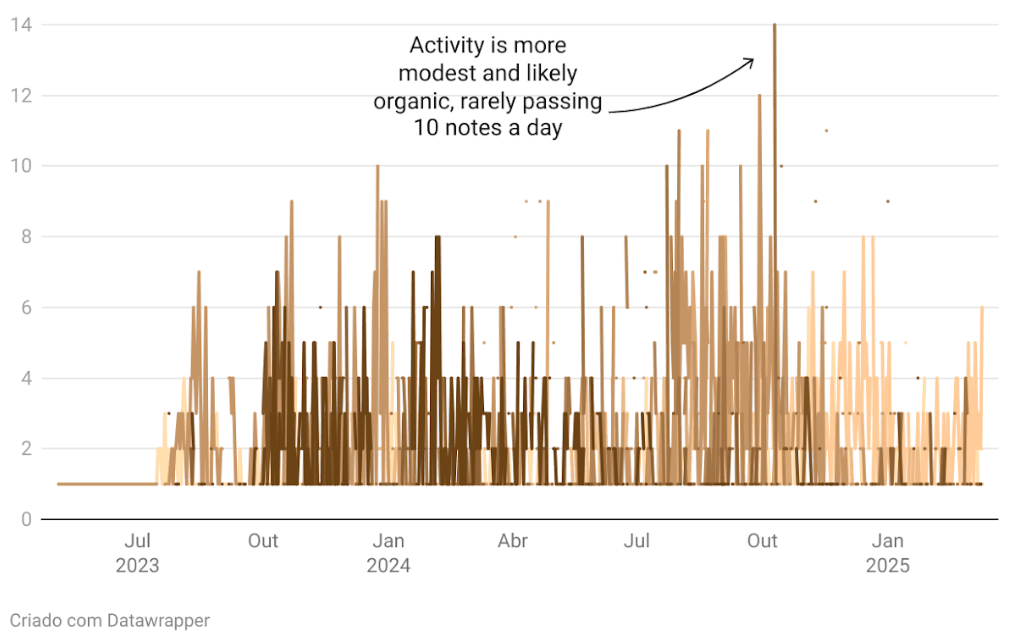

Spanish: Narrow Focus, Modest Output

In the Spanish-language universe of Community Notes, top contributors are fewer and less active. The leading account submitted 913 notes during the analyzed period, mostly addressing political misinformation about Nicolás Maduro (Venezuela). Its publication rate is 10.7%.

Other top Spanish contributors show a broad range of effectiveness – some with no notes published at all, while others reach up to 31.9% of notes published.

Daily Activity of the Top 10 Contributors in Spanish

9. RECOMMENDATIONS

Data Transparency:

X’s Community Notes dataset is open, but accessibility is very limited. Analyzing the data requires advanced infrastructure and technical expertise.

Recommendation: Companies should endeavor to make the public data they share filterable and available for download in parts, as well as in bulk. A system that allows researchers to navigate notes and to view which notes go with which posts through search could also be helpful for understanding trends and context of implementation.

Information-Sharing:

X’s Community Notes dataset lacks information necessary for drawing strong conclusions about metrics of success for publication.

What does consensus mean in practice? How many contributors must agree for a note to reach consensus. Where do most contributors reside? What is their demographic or ideological make-up? None of these questions are clearly answered by terms of service or the data.

Recommendation: To the extent companies are relying on more subjective metrics of success such as “consensus,” “diversity of perspectives,” and other measures, such terms should be clearly defined and the information about trends disclosed to Community Notes participants, researchers and regulators. Information to be disclosed can include the number of contributor/reviewer inputs needed, the percentage of inputs required from each side for consensus of agreement or disagreement to be reached, how many notes total were labeled as helpful or not helpful and why, and other broader trends related to consensus.

Recommendation: While disclosing personally identifiable information about contributors is out of the question because of privacy concerns, companies should consider disclosing trends, including but not limited to contributor demographic make-up and geographic breakdowns of contributors. Companies should also consider making available language labels that allow researchers to study language use without needing to use external tools to do so.

Language Improvements:

English and Spanish stand out as the top two most-used languages in the Community Notes program. English-language notes account for more than 60% of submissions, while Spanish represents less than 10%. Spanish participation surged when X opened Community Notes to users outside of the U.S. in 2023, but has since plateaued. Meanwhile, English contributions have climbed.

Recommendation: Companies must elevate notes made in languages other than English to boost visibility of contributions from the majority world. In specific, companies should prioritize elevating visibility of notes submitted in Spanish, the official language of over 20 countries and territories around the world and the second most used language in Community Notes. To the extent language labels can be applied within the dataset, companies should include language breakdowns in transparency reporting each year for, at a minimum, the top five most used languages in which notes are submitted.

Backlogs and Bottlenecks:

The vast majority of submitted notes – more than 90% – never reach the public. In early 2025, over 17% of English notes and 15% of Spanish notes remained unevaluated. Some were rated “not helpful,” and dismissed. But many are simply never rated at all, leaving them stranded in the system without ever entering a decision pipeline. For a program marketed as fast, scalable, and transparent, these figures should raise serious concerns.

Recommendation: Companies should develop a system for managing, merging, or archiving unevaluated Community Notes. Companies should consider how they can assure the notes are put in front of contributors after initial submission on a cadence, and offer insights on why they may not be being seen.

Speed:

Although the time it takes a note to go from submission to publication has improved – from over three months in 2022 to an average of 14 days in early 2025 – an average of 14 days is still far too slow to counter viral online harms, which typically spread within hours.

Recommendation: From the perspective of speed alone, companies must recognize that community-driven moderation cannot be the only, or even the main, approach to curbing the spread of online harms on their platforms. Consensus is hard to reach at scale. It is even harder to reach quickly. Despite recent developments, companies must go back to investing also in moderation by fact-checkers, local journalists and/or other professional editors that have no personal stakes in the notes they provide.

Recommendation: Regular users of X cannot see when a Community Note was originally submitted or approved for publication. Companies should consider disclosing the time it took a note to go from submitted to published as people process content of posts and the notes that go with those posts.

Detection of Automation:

In English, the most prolific contributor of Community Notes appears to be an automated account flagging cryptocurrency scams. The contributor offers tens of thousands of submissions, but his notes have a low publication rate.

Recommendation: To the extent AI technologies become more prolific and sophisticated, Community Notes contributors will no doubt find ways to use AI in their moderation. Companies implementing community-driven models of content moderation must think through guardrails for assuring AI is being used responsibly, if at all, and that any accounts doing so are disclosing the use.

10. CONCLUSION AND NEXT STEPS

As the community-driven content moderation model gains momentum, this deep dive, one of multiple DDIA hopes to do, specifically documents key functionalities of Community Notes and evaluates how note publication differs across English and Spanish. The analysis offers a data-based perspective on the make-up of the public data available, including the number and trends related to notes submitted to the program, notes published by the program, and top contributors.

As governments and tech companies debate how best to balance free expression, civic trust, and curbing online harms, Community Notes can no longer be seen as an X experiment. Like it or not, this model has become a global prototype serving as a benchmark for other companies. Understanding how Community Notes works – who the program serves, where it falls short, and what can be improved – is critical. Future analyses will look at the content of Community Notes and the posts that receive such notes to the extent possible. Both worlds are limited for analysis by X’s infrastructure of data sharing.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Roberta Braga founded the Digital Democracy Institute of the Americas (DDIA) in 2013 to strengthen a healthier Internet for Latinos and Latin Americans through behavioral and narrative research, capacitybuilding, and policy. Roberta brings over 13 years of experience working in U.S.-Latin America foreign policy, democracy-building and campaigns and communications. She was director for counter-disinformation strategies at Equis, a set of organizations working to better understand the Latino electorate in the United States, and served as deputy director for programs and outreach at the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center, where she led programming on election integrity across Brazil, Mexico, and Colombia, as well as in Venezuela. Roberta was awarded the HTTP Tech Innovadores Award in 2025 for her contributions to advancing inclusive digital spaces and tech-driven advocacy, and was named a Top Woman in Cybersecurity in the Americas by Latinas in Cyber and WOMCY in 2023. Roberta has an MA in Global Communication with a focus on Public Diplomacy from The George Washington University and a BA in Journalism and International Security from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Cristina Tardáguila is a senior research consultant for the Digital Democracy Institute of the Americas (DDIA). Cristina is the founder of Lupa, Brazil’s largest fact-checking hub, and LupaEducação, the country’s first media literacy initiative. A journalist working on countering misinformation online since 2014, Cristina currently researches online harms and writes weekly newsletters about breakout narratives impacting Latinos for the Digital Democracy Institute of the Americas and on trends in public WhatsApp and Telegram groups in Brazil for Lupa. She previously served as Associate Director of the International Fact-Checking Network at the Poynter Institute and Senior Director of Programs at the International Center for Journalists. Between 2019-2021, Cristina coordinated the world’s largest collaborative fact-checking project, the #Coronavirus Alliance, and, alongside fellow fact-checkers, was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2021. Tardáguila holds a degree in Journalism from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), a Master’s in Journalism from Rey Juan Carlos University in Spain, and an MBA in Digital Marketing from Fundação Getulio Vargas (FGV-Rio).

Marcelo Soares is a research consultant for the Digital Democracy Institute of the Americas (DDIA). He is founder and editor of Lagom Data, a data journalism studio in Brazil that specializes in collecting, analyzing, contextualizing, visualizing, and explaining public interest data for public policy. Marcelo served as the very first audience and data editor in Brazil’s news history, at Folha de S.Paulo, Brazil’s largest newspaper. He is also a founding member and served as the first executive manager of the Brazilian Association for Investigative Journalism (ABRAJI). As a freelance journalist, Marcelo has written for The Los Angeles Times, Wired.com, El Pais, and others.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

DDIA Executive Director Roberta Braga would like to thank the multiple experts who contributed to the making of this research report. A special thank you goes to DDIA senior research consultant Cristina Tardáguila for her creative research ideas, deep curiosity, and fearless energy. Muito obrigada to Marcelo Soares for his deep expertise and largescale contributions to analyzing the data necessary for making this report a reality. Thank you also to the DDIA board and advisory council members who offered their feedback and guidance in the preparation of this report, and to Daniela Naranjo, for her project management skills, speed, and ability to keep the team organized and on track. Dani truly is one of the best jane-of-all-trades out there. DDIA also thanks Katie Harbath and Tim Chambers for their listening ear and insights, and Donald Partyka for his beautiful design work.

Download the Report:

Download